Ep. 30

Patrick McKeown has been teaching about breathing since 2002. As a lad, Patrick had difficulties with asthma and inattention in school. Strikingly, he left academia at the age of 14. “Mindfulness” has become a buzzword over the last few years, and one of the many aspects of it is breathing. While there is a multitude of techniques to choose from, not many of them are backed by science. Tackling this issue is world-renowned breathing coach and best-selling author, Patrick McKeown. We start by discussing how Patrick fell into the world of breathing, from his challenges as a teenager, to how the idea of the Oxygen Advantage was born. Join us today to find out what the science says about breathing and the areas that we need more data. Discover the link between mouth breathing and sleep, and how this affects your mental wellness and physical performance. Learn about the underlying physiology of nasal breathing compared to mouth breathing, and how the BOLT score works. Andrés describes the breathing techniques he uses to help improve his free-diving and cycling, while Patrick breaks down the physiology behind breath holds. We touch on what VO2 Max means, and how it is linked to your breathing and EPO. Find out why Patrick trusts those with grey hairs (experience), the lessons he’s had to learn along the way, and how his perspective has changed over time. For all this and more, tune in today!

“The Oxygen Advantage was born to present a high-performance breathing technique, to change states, and to change physical performance”

https://oxygenadvantage.com/patrick-mckeown-3/

The Breathing Cure

By: Ariel Kamen, BSN, RN

Complete and utter exhaustion day in and day out. Despite turning off your phone and blacking out the windows every night, you likely wake up each morning feeling fatigued, restless, and unrecovered. Luckily, Patrick McKeown, Know Your Physio’s breath expert, may hold the solution to this suffering.

Historically, the simplest solution is usually the most regarded. “People do not consider their breath when in poor health circumstances,” says Peter Mckeown, “No matter how many biological tests, images, or studies have been done, virtually no doctor can explain why so many people wake up with dry mouth and enervation after a low-grade night of sleep.” These days, poor sleep quality is attributed to the social anxieties surrounding the overstimulation of late-night media (Cavalcanti et.al, 2021); yet according to Patrick Mckeown, the real culprit is even more dangerous.

Sleep quality reflects a person’s ability to fall asleep, stay asleep, and enter into the various rejuvenating sleep cycles for the full duration (Schroeder & Gurenlian, 2019). Sleep quality is highly influenced by our breath. Dysfunctional breathing patterns, as those seen in asthmatic individuals and sleep disorders often coexist in the same individual (Reiter, et, al, 2021). “The most effective thing we can do to enhance sleep quality is breathe in and out through our nose,” says Patrick Mckeown. He follows up by rhetorically asking listeners, “How can we address ‘agitation of the mind’ without addressing the breath?”

The physiological superiority of nasal breathing has been brought to light by our insightful guest on KnowYourPhysio podcast Episode 30. In this episode, Patrick Mckeown shares unusual stories about his breath experiments. His Oxygen Advantage teaches the science, how to implement, and the numerous benefits to taping your mouth shut before bed.

Mouth breathing is the cause of many issues like dry mouth and poor immunity (Musseau, 2016). Holding the mouth open at rest exposes mucous membranes to atmospheric air which dries out the tongue and palate respectively. Snoring, obstructive sleep apnea, and sustained fatigue are some manifestations of mouth breathing, as is dry mouth and lower back pain, yet mouth breathing has become so common that the general public has not caught up with the reality that it is a problem. Patrick Mckeown’s discussion on mouth breathing falls under the umbrella term ‘dysfunctional breathing.’ Before looking further into dysfunctional breathing, let’s review the physiology of breathing and learn how to measure the breath !

Physiology of Breathing

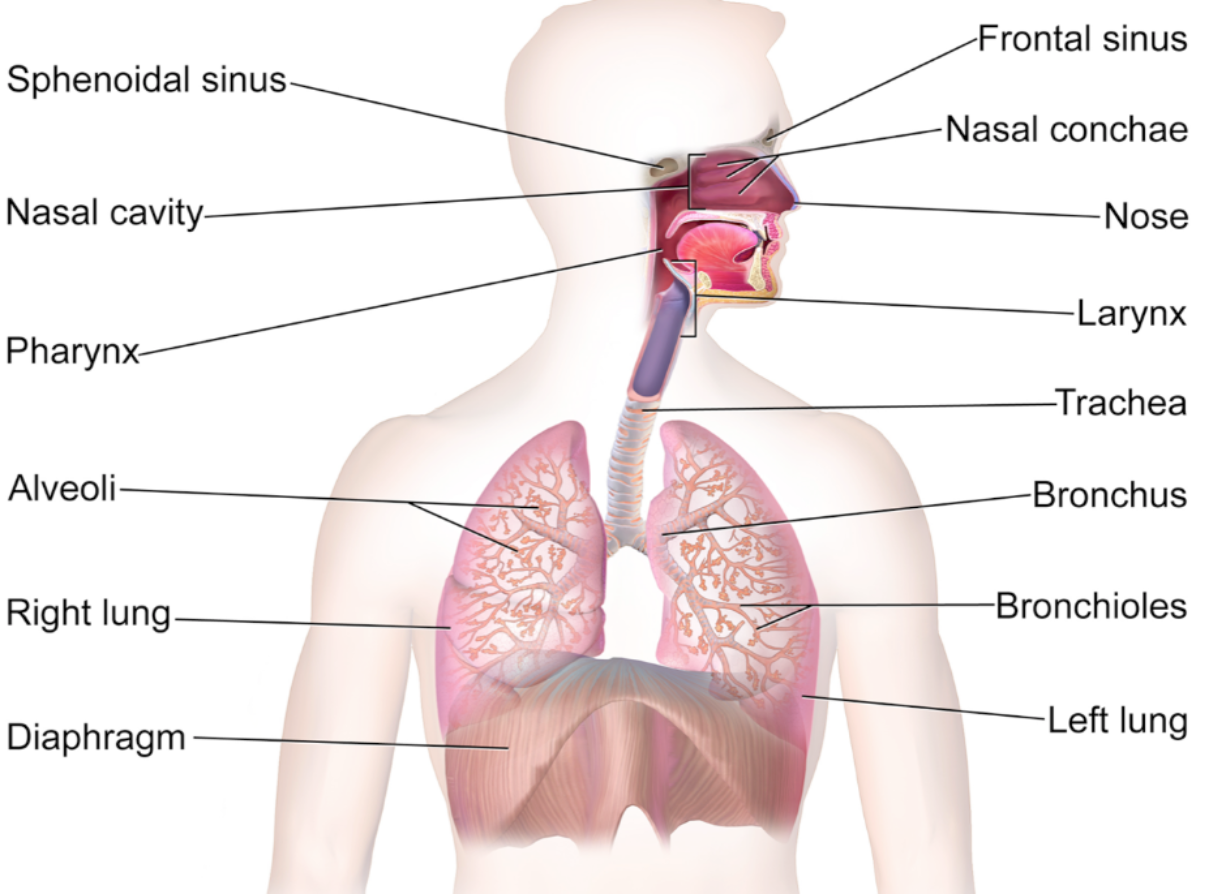

Air vacuums into our nostrils, behind our tongue and down into the trachea to penetrate the alveoli at the deepest portion of the lungs. Diaphragmatic relaxation returns our muscular dome to its original shape and rhythmically guides gas exchange.

The inhalation and exhalation of air is achieved using the respiratory organs outlined in Diagram A. If you look closely, you may notice that the oral cavity (mouth) is not included as a respiratory organ, and is in fact a digestive organ.

The process of respiration is divided into three parts: ventilation, perfusion, and diffusion.

- Ventilation is the movement of air into the lungs.

- Perfusion is the movement of blood through the pulmonary circulation, including the pulmonary capillaries around the alveoli, where gas exchange takes place.

- Diffusion is the movement of O2 and CO2, driven by the partial pressure of the gasses. Respiration starts and ends in the nose, any other technique that strays from the nose is a compensatory design of breathing (Wolters, 2014).

To quickly dismantle any uncertainty about nasal breathing, we must become familiar with the gross anatomy of the larynx where a little flap of tissue called the epiglottis is located at its superior portion. The sole role of the epiglottis is to cover the trachea and prevent any solid objects from entering the airway. A common phenomenon called aspiration occurs when something goes down the wrong pipe. Well, in these moments of aspiration, the epiglottis malfunctions — usually as a result of eating or drinking too fast. As a protective counter-mechanism, the body begins to cough and tear up with the intent to dislodge the airway of any non-gaseous substance.

The physiological superiority of nasal breathing is because of its direct pathway into the trachea, which Patrick describes as being “the size of a straw.” Depicted in Diagram A, the trachea evolves into one large bronchus below the neck as it enters the thorax (chest). The bronchus then bifurcates into bronchi and spans out into bronchioles throughout the lungs to pipeline atmospheric air throughout the entire surface area of the lungs. At the functional unit of respiration is the alveoli. These tiny sacs are gloved by pulmonary capillaries where biochemical gas exchange occurs. Below the lungs is an underrated skeletal muscle– the diaphragm– acts as a divider between the chest and the abdomen.

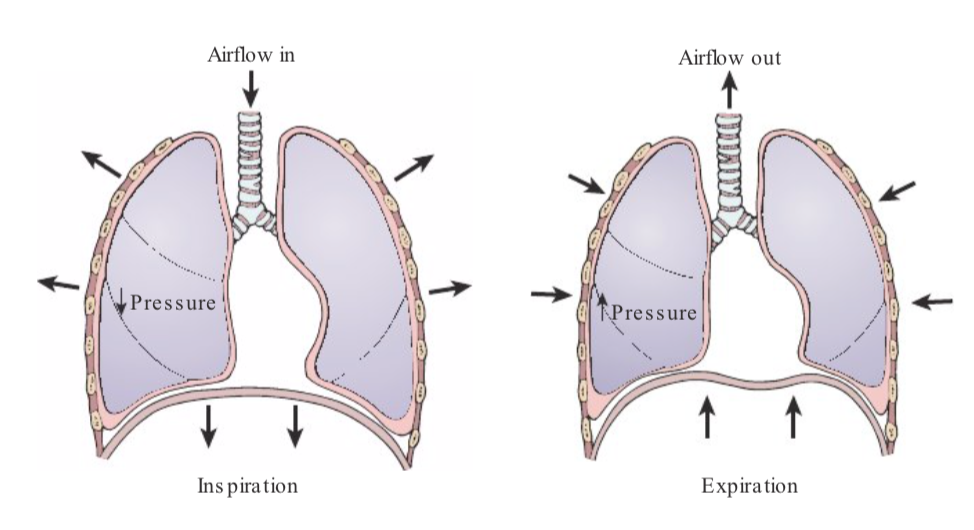

The diaphragm is the principal muscle of inspiration (airflow in). It is dome-shaped at rest and flattens during exhalation (airflow out), depicted in Diagram B.

Air is best brought into the lungs by the nose, all while the diaphragm moves to create space for lung expansion. When air is expelled out of the nostrils, the diaphragm relaxes into its natural dome position. During normal volumes of inhalation, the diaphragm moves approximately 1 cm, although forced inhalation can increase diaphragmatic expansion to 10 cm.

Not only is the diaphragm relevant for breathing, it is also a key contributor to spinal stability. Our ability to hold our backs upright and erect is important to create the most patent pathway for airflow and circulation of both blood and cerebrospinal fluid. Streamline circulation manifests as feelings of concentration, ease, and acceptance of the task in front of us, amongst other parasympathetic states of the nervous system.

The Oral Cavity

Mouths are divinely designed for eating, speaking, and drinking. Breathing through the mouth causes the diaphragm to move in the opposite direction of its design. Gasping air into the mouth inflates the abdomen and pushes the diaphragm upwards; this restricts the lungs from being able to expand. Patrick Mckeown describes it as follows, “mouth breathing typically activates the upper chest and faster breathing which forces the nervous system into a more sympathetic state.” Mouth breathing suffocates the body and brain at different degrees depending on if the person has experienced trauma, is in a panic state, or at rest.

How does nasal breathing actually work?

“It’s not how much oxygen you’re getting, it’s about the delivery.” As previously mentioned, the nasal cavity leads directly into the airway, when we breathe through our mouth, it may feel like we are taking in a larger amount of air but the delivery is few and weak. Taking in air through the nose gets oxygen right where it needs to go, regardless of depth.

Shifting your attention to nose breathing may make you feel short of breath. Air hunger is stronger with nose breathing, but this sensation diminishes over time. Air hunger is felt when there are higher levels of CO2 in blood. Nasal breathing, over time improves the body’s CO2 tolerance and reduces the ventilatory response, thus breathing becomes lighter. Air into the nose dilates blood vessels and improves overall circulation to the body, especially the throat muscles that function to hold the airway open. CO2 levels in the blood are the primary stimulus to breathe. When levels of carbon dioxide increase, Hgb releases more oxygen into the blood.

“I think it;s a great shame that people do not know how to breathe optimally”

– Patrick Mckeown

Dysfunctional Breathing

Functional breathing refers to the proper physiological mechanisms surrounding the breath. Conversely, dysfunctional breathing refers to pathological changes in one’s breathing patterns (Watson, Ionescu, Sylvester & Fuld, 2021). These changes lead to a feeling of breathlessness and include alterations in the three pillars of functional breathing.

- Biochemical (gas exchange & blood stream content)

- Entire concentration in the blood (PaO2) increases 10% with mouth closed (Lundberg et. al, 1996)

- Biomechanics (inflation & deflation of the lung tissue)

- Psychophysiological (breath’s effect on mood)

Patrick says that “1 in 5 people have dysfunctional breathing”. Dysfunctional breathing contributes to manifestations such as dizziness and heart palpitations (Vidotto, Carvalho, Harvey & Jones, 2019). If you thought it couldn’t get more complex, Mckeown mentions that, “females may be predisposed to dysfunctional breathing at different times throughout the menstrual cycle because of hormonal changes.” Another contributor to dysfunctional breathing is the stress of artificial light exposure on our eyes and for our brains.

“The influence just your breath can have” – Patrick Mckeown

What happens to our inner body when we change our breathing ?

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a hormone produced by the kidneys. Erythropoietin sends a message to bone marrow to create more red blood cells (RBCs). Oxygen is carried throughout the bloodstream by RBCs. Hematocrit (Hct) is a laboratory value that measures the percentage of overall oxygen carrying blood. Average hematocrit values for adult males (47%) differs from adult females (42%). There is a positive correlation between hematocrit and VO2 max – the maximum rate of oxygen consumption measured during incremental exercise.

To increase hematocrit levels, more oxygen must be carried by the RBCs. The spleen contains 80% of oxygen carrying RBCs, and a breath hold of 30 seconds releases RBCs from the spleen. The benefits of this practice persists for 10 minutes. Note: breath holding is not suitable for pregnant women and people with anxiety, panic disorder, or cardiovascular disease .

Carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations serve as the body’s alarm to breathe. Human lungs need 5% CO2 at baseline. Anything deviation from this causes acid base imbalances within the bloodstream. Two organs function to compensate for acid base imbalances, these are the kidneys and the lungs. Either EPO is released from the kidneys or the respiratory rates changes amongst the lungs. Hyperventilation is a stressor to the human body, although it can be a protective factor of achieving acid-base balance. Eustress becomes distress when these techniques are used improperly.

Breathing Throughout the Lifespan

Patrick Mckweon describes developmental changes of the human face as a result of mouth breathing because, “the tongue is falling back into the throat which covers the airway, while the mandible (lower jaw) is pushing down on the airway,” he says, “the nose is the only organ to protect the lungs, moistens air, regulate volume, redistribute blood throughout the lung, and have antibacterial and viral benefits from nitrous oxide.” Humanity is gasping for information on how the body functions.

To make matters worse, “pediatricians are overlooking mouth breathing,” says Mckewon. “To ensure optimal development of the face, the mouth must be closed, lips together, breathing in and out through the nose with the tongue resting on top of the mouth.” The human face is changing due to dysfunctional breathing and the food we eat. Attention deficit rates among students are rising and Patrick attributes this to mouth breathing. He says, “How on earth can you achieve good concentration and attention span if you have functional breathing and poor sleep? Both go hand and hand.” Addressing breathing in children is one way to change the health outcomes of the next generation.

Measure of Breath

Patrick Mckweon’s Oxygen Advantage explains step by step how to measure our breathBody Oxygen Level Test scores the degree of breathlessness during rest and exercise.

To accurately measure a BOLT Score, start by “having the person sit for 5 min breathing normally, then pinch their nose and time in seconds, the first definite desire of needing to breathe… If the BOLT score is >25 seconds there is an 89% dysfunctional breathing is not present.”

The Dangers of Mouth Breathing

Modern day breathing mechanics divide breathers into two categories: Nose Breather or Mouth Breather. Mouth breathing is dangerous for prolonged periods of time since it deprives the diaphragm of its soulful movement. There is not enough oxygen for the brain during mouth breathing. It is associated with an inability to concentrate & nervousness at rest. Nose breathing provides air direct flow down the pipes, and releases nitric oxide to dilate the pipe’s diameter and the muscles of the neck that are holding the airway open. For gas exchange to occur, oxygen needs to reach the alveoli.

Prolonged periods of mouth breathing steals blood from the legs to help supply flow to the diaphragm. The buildup of hydrogen ions in the bloodstream due to inadequate gas exchange causes the legs to collapse. This diaphragm fatigue phenomenon is commonly seen in Olympic track and field athletes. Energy cost increases when we waste air, thus not properly delivering oxygen to the deep alveoli. Nasal breathing is shown to delay lactic acid and fatigue by properly oxygenating the visceral organs.

Failure to engage the diaphragm while we breathe causes instability of the spine and can manifest as back pain. Optimal levels of intra-abdominal pressure cannot be achieved during mouth breathing. Another attribution of mouth breathing is exercise induced bronchoconstriction (i.e. airway narrowing) which can be combated through nasal breathing. Exercised induced bronchoconstriction persists until BOLT score is over 25 seconds.

Actionable Steps

It is crucial to understand resonance frequency as the different ways we breathe at rest and during activities including but not limited to; sleep, exercise, and work.

Taking the time to practice functional breathing in and out of your nose may slightly increase your energy level.

To achieve flow state, we need concentration & if we don’t get our sleep right, then we cannot achieve a flow state. Mindfulness says don’t change your breathing, Patrick Mckeown says do change your breathing. Experiencing the restorative benefits of deep sleep can be optimized through functional breathing.

- First, consider if you have dry mouth or wake up exhausted despite the amount of sleep you got

- If yes, nose breathing may be for you

- Measure your BOLT score by watching this video https://oxygenadvantage.com/measure-bolt/

- Do your warm up with your mouth closed

- Seal your mouth closed before bed using Patrick McKeown’s tape https://oxygenadvantage.com/product/myotape-2/

Resources

Cavalcanti, L., Lima, R. A., Silva, C., Barros, M., & Soares, F. C. (2021). Constructs of poor sleep quality in adolescents: associated factors. Cadernos de saude publica, 37(8), e00207420. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00207420

Lundberg, J. O., Settergren, G., Gelinder, S., Lundberg, J. M., Alving, K., & Weitzberg, E. (1996). Inhalation of nasally derived nitric oxide modulates pulmonary function in humans. Acta physiologica Scandinavica, 158(4), 343–347. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-201X.1996.557321000.x

McKeown, P., O’Connor-Reina, C., & Plaza, G. (2021). Breathing Re-Education and Phenotypes of Sleep Apnea: A Review. Journal of clinical medicine, 10(3), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10030471

Musseau D. (2016). Mouth Breathing and Some of Its Consequences. International journal of orthodontics (Milwaukee, Wis.), 27(2), 51–54.

Nagpal, M. S., singh, J., Khushi, Shreya, User, Samruddhi, Ashwini, shahid, S., Nisha, Pandey, Y., Alee, H., Mittal, V., & Ali, M. M. D. A. (2020, August 19). Respiratory system in humans – class 10, Life Processes. Respiratory System . Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://classnotes.org.in/class-10/life-processes/respiratory-system-in-humans/

Reiter, J., Ramagopal, M., Gileles-Hillel, A., & Forno, E. (2021). Sleep disorders in children with asthma. Pediatric pulmonology, 10.1002/ppul.25264. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25264

Schroeder, K., & Gurenlian, J. R. (2019). Recognizing Poor Sleep Quality Factors During Oral Health Evaluations. Clinical medicine & research, 17(1-2), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.3121/cmr.2019.1465

Watson, M., Ionescu, M. F., Sylvester, K., & Fuld, J. (2021). Minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production in patients with dysfunctional breathing. European respiratory review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society, 30(160), 200182. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0182-2020

Vidotto, L. S., Carvalho, C., Harvey, A., & Jones, M. (2019). Dysfunctional breathing: what do we know?. Jornal brasileiro de pneumologia : publicacao oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisilogia, 45(1), e20170347. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-3713/e20170347